Quantum mechanics: the double-edged sword of its development that we commemorate today

A few days ago marked the centenary of the beginning of the quantum revolution , a radical way of understanding physics based on observing the apparent disorder displayed by electrons around the nucleus of an atom. It was on July 9, 1925, when the 23-year-old Werner Karl Heisenberg handed a copy of his work to Max Born, a physicist and mathematician whose assistant he was at the University of Göttingen. In the aforementioned work, Heisenberg studied the behavior of the electron in each of its jumps. With the strange beauty traced by mathematical laws, Heisenberg handled tables—Göttingen matrices—where the arrival and departure orbits are represented in columns and rows; each jump of the electron affects these two orbits. From now on, instead of predicting certainties, probabilities are predicted. With this, deterministic laws are excluded from this new way of understanding physics.

Thus begins a new scientific era that will project its chiaroscuro throughout the years and continues to this day. Because the double-edged sword that threatens the grammar of the world, where unpredictability lies, we owe to quantum mechanics. On the one hand, thanks to its technological effects, we can communicate through mobile devices; without going any further, we can read this same article on the other side of the world.

And while we owe much of this initially to the young Heisenberg, who delved into the magic of electron leaps, it's also worth adding that quantum mechanics combined with chemistry and engineering to achieve the destructive power of the atomic bomb. There we have the other side, the cutting edge.

With this approach, the effects of applying this new physics lead us to assimilate reality differently, revising our understanding of it. Because the world becomes an inhospitable place where, at any moment, catastrophe can strike. It is now eighty years since that day—August 6, 1945—when the United States dropped the Little Boy bomb from the skies of Hiroshima.

Now, after the horror, let's go back for a moment to 1925, when the world of the electron was still coming and going in the innocent dimension of a few pages written in a "crazy" manner, according to Heisenberg himself in the note to the work he submitted to Max Born. After reading it, Max Born found it so interesting that he sent it to the journal Zeitschrift für Physik . With that, the mechanisms of chance were set in motion.

We've already said that we're in 1925, a year of chiaroscuro and morbidity, of ghosts and smoke signals for Europe and the world. It was the year Hitler's pamphlet, Mein Kampf, was published. It was also the year Stalin came to power and the year Franco, then a colonel, gained experience in the Alhucemas landings. We're talking about an oppressive and senseless time that Kafka would take to its final narrative flames with his posthumous work , The Trial, a story in which uncertainty becomes a bureaucratic nightmare. The hidden grammar of reality would soon reveal itself.

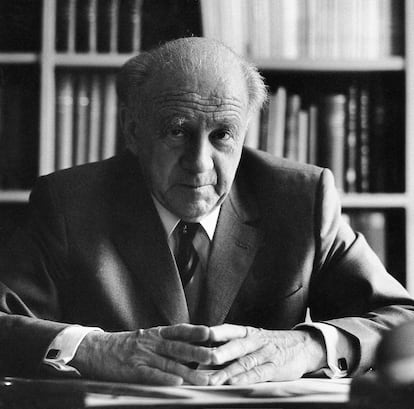

The Stone Axe is a section where Montero Glez , with a desire for prose, exercises his particular siege on scientific reality to demonstrate that science and art are complementary forms of knowledge.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read it on the other device.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade to Premium, so you can add another user. Each user will log in with their own email address, allowing you to personalize your experience with EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who's using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you decide to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed indefinitely on your device and the device of the other person using your account, affecting your reading experience. You can view the terms and conditions of the digital subscription here.

Journalist and writer. His notable novels include "Champagne Thirst," "Black Powder," and "Mermaid Flesh."

EL PAÍS