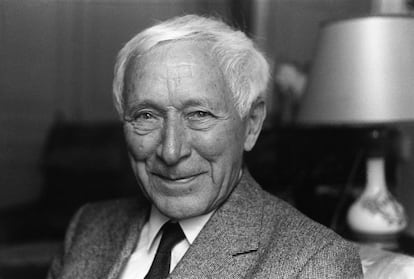

How Ernst Jünger nearly reached 103 years old

These are strictly opinion pieces that reflect the author's own style. These opinion pieces must be based on verified facts and be respectful of individuals, even when criticizing their actions. All opinion pieces by individuals not affiliated with the EL PAÍS editorial staff will include, after the last line, an author's name—regardless of their prominence—indicating their position, title, political affiliation (if applicable), or primary occupation, or any occupation that is or was related to the topic addressed.

Reading his diaries is an encouragement to scientific knowledge

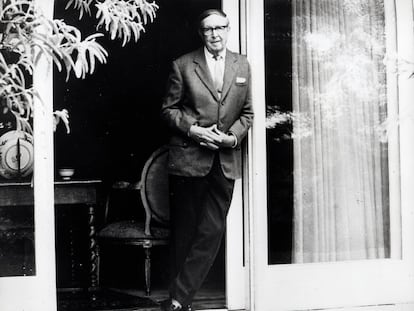

The day after turning seventy, with biblical age upon him, Ernst Jünger begins a diary that the Tusquets publishing house published under the title After Seventy (translated by Andrés Sánchez Pascual) and which begins on March 30, 1965 with a walk through Wilflingen, a town where the German thinker lived in seclusion with his wife Liselotte, whom he affectionately called Taurita because she was born under the sign of Taurus.

It is fascinating to observe how Jünger's thinking blends mythology with scientific analysis. Reading his diaries leads us to that elusive point between two seemingly opposing yet complementary worlds. In this way, Jünger surprises us with his precision and sensitivity in perceiving the signs of his surroundings. For example, on this first walk with which he opens the diary, Jünger encounters a lizard. He finds it on one of the rocks on the hill where the "Treasure Castle" stands. It is a real image that, thanks to his interpretive skills, Jünger transports to a fictional dimension , culminating in the description of the reptile's skin as "brown with green stripes." Jünger then wonders if this might be the lizard's first spring outing; it seemed drowsy, as if still retaining remnants of its winter slumber. Jünger approaches it with great care and strokes it.

There is a feeling of resurrection in spring, Jünger seems to be telling us; a feeling that enhances “vital existence.” Hibernation, for Jünger, was the closest thing to “enjoying time stretched to the limit of perception.” With a precise syntax on par with Borges or Canetti —to name two supreme examples—Jünger allows himself to be guided from his German residence to the Far East on a five-month journey. Driven by curiosity, he discovers botanical species such as the Ravenala, known as the traveler's palm, which opens its leaves like a fan and whose canopies rise above the walls of Singapore's gardens.

In another of his entries, Jünger explains that warm-blooded animals are more prone to death than cold-blooded ones because, he says, they must maintain their temperature within narrow limits. Excess heat leads to fever, and deficiency to frostbite, and it is here that Jünger points to air conditioning as a “cosmic provocation.” To clarify, Jünger refers us to the beginning of the world when “creatures lived within Gaia as in a mother’s womb,” immersed in the warmth of swamps or the sea. When cooling occurred, Jünger continues, the organisms that survived did so thanks to their adaptation, achieving a new equilibrium with the environment. This is why warm-blooded animals like seals survive in cold waters, their existence leading to the regressive form of fish that, “to avoid freezing, have acquired a protective covering.”

With these forays into nature, Jünger takes us from curiosity to knowledge on an unrepeatable journey. His diaries, and especially this volume we are discussing here, are a veritable scientific declaration; an example of how to travel a path where prediction and surprise alternate until wisdom is attained.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read it on the other.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade your subscription to Premium so you can add another user. Each person will log in with their own email address, allowing you to personalize your experience on EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who is using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you choose to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed on both your device and the other person's device indefinitely, affecting your reading experience. You can view the digital subscription terms and conditions here.

Journalist and writer. Among his novels, titles such as 'Thirst for Champagne', 'Black Powder' and 'Mermaid Flesh' stand out.

EL PAÍS