One hundred years since the Scopes monkey trial, the condemnation of the teaching of evolution

One hundred years ago, in rural America, a trial took place that arguably deserves a movie, if it weren’t for the fact that it’s already been made: in 1960, Stanley Kramer directed Inherit the Wind , based on the play of the same name by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, which fictionalized the famous trial in which John Scopes, a young high school biology teacher, was prosecuted for teaching Darwinian evolution . The “Scopes Monkey Trial,” as it became known, was a milestone in the eternal battle of rational scientific thought versus belief-based denialism, a conflict that continues a century later.

The story begins on a Sunday in 1921 with a sermon at the Baptist Church in Dayton, Tennessee. A preacher recounts how a woman lost her faith after attending a college course on evolution. Among the parishioners is a rough farmer named John Washington Butler, who is not content with being scandalized like the others; terrified that one of his children might follow in that woman's footsteps, he runs for the Tennessee House of Representatives the following year with a campaign promise: Darwin's theory will not be taught in any public school.

No sooner said than done: Butler drafted the law on the morning of his 49th birthday, after breakfast, sitting in front of the fireplace. The text condemned any professor who taught "any theory which denies the story of the Divine creation of man as taught in the Bible," for example by stating that "man is descended from a lower order of animals," to a fine of up to $500—about $9,000 at today's exchange rate.

The bill passed the House by an overwhelming majority of seventy-one to five. Before passing through the Senate, the debate spilled into the streets, but that didn't stop the bill from being ratified and signed by Governor Austin Peay on March 21, 1925.

A political give and takeIt wasn't just religious conviction that drove the Butler Act; some representatives simply preferred not to upset their constituents. As for Peay, considered a progressive Christian, he had his own reasons. According to science historian Adam Shapiro of Birkbeck University in London and author of Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools (University of Chicago Press, 2013), compulsory schooling was expanding in the US at the time. For Peay, the law was "partly a political compromise," Shapiro says. "Accepting it allowed the governor to push through progressive laws to build more schools and train more teachers" without raising eyebrows in religious communities.

In any case, Peay hoped the new law would go unnoticed, given that Darwinism had already been around for half a century and was already extremely popular. He was wrong: Tennessee's ban prompted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to publicly offer to defend any teacher who was sued, seeking to prove the law unconstitutional in court.

Echoes of the ACLU's announcement reached back to Dayton, where an engineer named George Rappleyea accepted evolution and opposed the law. But he saw the resulting commotion as an opportunity to put the small town in the spotlight, which would attract a large audience and help revitalize the then-precarious local economy.

Rappleyea was the architect of Scopes's trial: not only did he convince local authorities to mount a case, but he also chose the defendant, since no one had yet been charged. He summoned Scopes, 24, who wasn't a tenured biology teacher but a football coach covering for an absence, and asked him if he had ever taught evolution. The young man wasn't even sure, but he was sure that the textbook discussed it—a book he hadn't chosen, but rather the state of Tennessee, which had outlawed its content. Scopes accepted the role of defendant and even encouraged his students to testify against him, which they did.

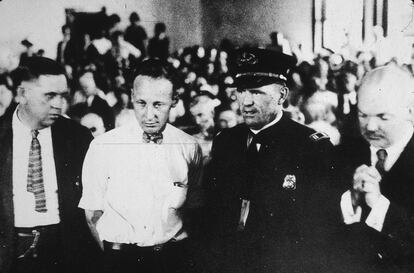

The first media trialThe trial, the first to be broadcast live on radio, took place from July 10 to 21, 1925. As Rappleyea had planned, Dayton became a grand carnival, complete with circus monkeys. Kramer's play and film immortalized the dialectical clashes between two charismatic characters, who in the fiction appear under assumed names. The agnostic lawyer and ACLU member Clarence Darrow represented the defense, and former Democratic presidential candidate and former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan represented the prosecution. Bryan was a Presbyterian fundamentalist who had led a crusade against the teaching of evolution in several states.

Darrow enlisted expert testimony from scientists and even called Bryan himself as a witness, putting him on the spot by highlighting the absurdity of literal interpretation of the Bible. But none of this was of any use; for Judge John Raulston, the only relevant issue was whether Scopes had broken the law. The jury found that he had, and the professor was fined $100, which was overturned on a technicality on appeal.

“After Scopes, no one was prosecuted again for violating Tennessee law,” Shapiro notes. In 1955, “Inherit the Wind” debuted on Broadway, reigniting the controversy over a law that was still on the books. When the ACLU petitioned for its repeal, the Tennessee government responded that the law was effectively dead, but that there was no interest in starting a political fight to repeal it. It wasn’t until, in 1967, another teacher, Gary Scott, filed a lawsuit against the Butler Act after being fired for violating it that the Tennessee Assembly took the opportunity to vote on its abolition, which the governor signed on May 18.

But the Tennessee case, while the most high-profile, was not the only one. The following year, in 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a similar law in Arkansas was unconstitutional. However, according to Shapiro, even in states without specific laws, "often not teaching evolution was simply the norm." The historian explains that in most schools, avoiding controversy was paramount. He adds: "Then as now."

Anti-evolutionism changes its name“Anti-evolution strategies have shifted in response to legal cases,” Shapiro continues. So-called Creation Science managed to circumvent obstacles by claiming to be based on observations of nature until it was declared unconstitutional in the 1980s; only to be replaced by Intelligent Design , “which argues against the sufficiency of evolution to explain life and doesn’t specify any theological suggestions about who or what the designer is,” Shapiro explains. In 2005, a new court case also struck down the teaching of this version; but, Shapiro says, academic freedom laws still protect professors from teaching whatever they see fit without restriction.

On the occasion of the centennial of the Scopes trial, Glenn Branch, director of the National Center for Science Education, writes in Scientific American that “the teaching of evolution has a bright future in the US.” Branch refers to surveys, according to which acceptance of evolution is now among the majority of the public, and among high school biology teachers it has grown to 67% (of the rest, 18% still offer creationism as an alternative). Will this trend be consolidated under Donald Trump's second term?

Evidence of this resilience is that in 2017, the placement of a statue of Darrow in Dayton—the one of Bryan was erected in 2005 —sparked opposition from a portion of the community . One neighbor told The New York Times that such an “atheist statue” could unleash a plague or a curse. Even today, in conservative rural America, evolution proceeds slowly.

EL PAÍS