I'm an NHS leader - but mum still suffered at hands of health service because she was black

A senior NHS leader has criticised the health service, saying his mother received a "black service, not an NHS service" as she died.

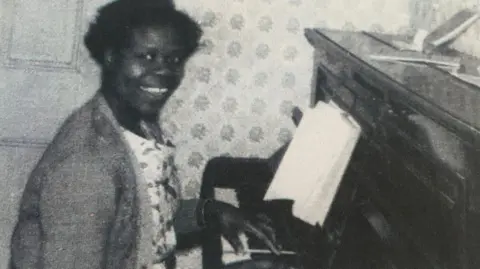

Lord Victor Adebowale, chair of the NHS Confederation, which represents health managers, described his mother Grace's death as "undignified".

The 92-year-old died in January of suspected lung cancer, although it was not detected until after her death.

Lord Adebowale said his mother's missed diagnosis, combined with the sub-standard care she received when admitted to hospital for the final time, had left his family upset and searching for answers.

The peer, who was also on the board of NHS England for six years, believes his mother's experience illustrates wider problems.

"My mum would have wanted me to tell her story because she is not the only one who will have faced these problems."

Lord Adebowale said he would not call the NHS racist, but instead believed it was riven with inequalities, particularly racial inequalities.

"It's the inverse care law. The people most in need of health and care are the least likely to get it - if you are black, if you are poor, if you are elderly and poor, there are inequalities in the system and people like my mum suffer."

The intervention by such a figure is significant. Lord Adebowale has held senior health roles for more than two decades and also helped establish the NHS Race and Health Observatory in 2021 to try to tackle inequalities experienced by black and minority ethnic patients in healthcare.

NHS England said it was working to improve access to services and tackle inequalities, which would form an "important part" of the 10-year health plan, expected to be published next month.

A spokesperson added: "Everyone - no matter their background - should receive the best NHS care possible. But we know there is much more to do."

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care echoed those comments, adding: "Our deepest sympathies are with Lord Adebowale for the loss of his mother."

Lord Adebowale's mother, who had three other children, emigrated to the UK in the 1950s from Nigeria and went on to work as a nurse in hospitals, the community and mental health services.

He describes her as a caring, compassionate and intensely committed nurse.

"She believed in the health service. It's people like her who help build the NHS, but, when she needed it, it wasn't there as it should have been.

"She had dementia and in the final five or six years was in regular contact with the health service. We cannot understand why she did not get a [cancer] diagnosis. She was in discomfort and pain – and had been for some time.

"She never got any treatment for cancer – it was only after she died we learnt she had lung cancer."

That was found during a post-mortem and subsequent tests have suggested that was the likely cause of her death, he said.

Lord Adebowale added that when his mother was taken to hospital the final time it was not easy to find her a bed. "The hospital was under intense pressure. She did not want to die in hospital in that sort of situation."

Lord Adebowale is not naming the NHS service involved in her care, saying he does not want to apportion individual blame, as his mother's experience was symbolic of a wider problem.

"I just think there are too many situations where people that look like me and shades of me don't get the service they deserve. It was not the dignified death that we would have wanted for her. It wasn't the death she deserved.

"I think she got a black service, not an NHS service."

Lord Adebowale, who for nearly 20 years was chief executive of Turning Point, a care organisation that supports people with substance misuse and mental health problems alongside those with learning disabilities, before becoming chair of the NHS Confederation in 2019, said there were multiple examples of inequalities in the health service.

He highlighted research showing younger black people waited 20 minutes longer on average in A&E than white people.

It also showed people from the poorest backgrounds were more likely to face year-long waits for routine treatment.

Other studies have suggested people from deprived communities are 50% more likely to have cancer diagnosed after a visit to A&E – such diagnoses are more likely to be at a later stage when chances of survival are lower.

He said while the promise of extra money for the health service made in this week's spending review was welcome, that alone would not tackle the inequalities.

"It a systematic problem – I don't want to blame any particular individual or my mum's local NHS.

"What happened to her could happen anywhere. We need to address inequalities in the health service and that requires leadership – not just money."

BBC