Guns, Race, and Profit: The Pain of America’s Other Epidemic

BOGALUSA, La. — Less than a mile from a century-old mill that sustained generations in this small town north of New Orleans, 19-year-old Tajdryn Forbes was shot to death near his mother’s house.

She found Forbes face down in the street in August 2023, two weeks before he had planned to move away from the empty storefronts, boarded-up houses, and poverty that make this one of the most troubled places in the nation.

Naketra Guy thought about how her son overcame losing his father at age 4 and was the glue of the family. She called him “humble” and “respectful,” a leader in the community and on the football field, where he shined.

Yet he could not outrun the grim statistics of his hometown. Bogalusa posts some of the worst health outcomes and poverty in Louisiana, a state that routinely ranks among the worst nationally in both. And Bogalusa has endured another indicator of poor public health: high levels of gun violence.

Since the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic, gun violence has shattered any sense of peace or progress here. Louisiana suffers the nation’s second-highest firearm death rate — and Bogalusa, a predominantly Black community with 10,000 residents, has seen dozens of shootings and a violent crime rate approaching twice the national average.

A nearby team refused to play football at Bogalusa High School in fall 2022, citing safety concerns.

Bogalusa’s mayor, Tyrin Truong, was elected in 2022 at age 23 on his promises to fix entrenched challenges: few youth programs and good jobs, and perpetual crime and blight.

“I ran for mayor because I got sick of seeing our city painted as mini-New Orleans,” he said, “due to the high levels of youth gun violence.”

In January, the Louisiana State Police arrested Truong, accusing him of soliciting a prostitute and participating in a drug trafficking ring that allegedly used illicit proceeds to buy firearms. He has said he is innocent. “I still haven’t been formally arraigned,” he told KFF Health News in late July, “and I haven’t been charged with anything.”

Every year tens of thousands of Americans — one every few minutes — are killed by gun violence on the scale of a public health epidemic.

Many thousands more are left to recover from severe injuries, crushing medical debt, and the mental health toll of losing loved ones.

Most headlines focus on America’s urban centers, but the numbers also reflect the growth of gun violence in places like Bogalusa, a pinprick of a town 75 miles north of New Orleans. In 2020, the gun violence death rate for rural communities was 40% higher than in large metropolitan areas, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Firearms are the No. 1 killer of children in the U.S., and no group suffers more than young Black people. More Black boys and men ages 15 to 24 in 2023 were killed in gun homicides than from the next 15 leading causes of deaths combined. Though overall U.S. homicides dropped sharply after the pandemic ended, adolescent gun deaths climbed even higher in the years after, according to research by Jonathan Jay, an associate professor in the School of Public Health at Boston University.

“It has all the markers of an epidemic. It is a major driver of death and disability,” Jay said. “Gun violence does not get the attention it deserves. It is underrecognized because it disproportionately impacts Black and brown people.”

Rather than bolstering efforts to save lives, federal, state, and local government officials have undermined them. KFF Health News undertook an examination of gun violence since the pandemic, a period when firearm death rates surged. Reporters reviewed government reports and academic research and interviewed dozens of health policy experts, activists, and victims or their relatives. They reviewed corporate earnings reports from gun manufacturers and data on the industry’s donations to politicians.

In polling published in 2023 by KFF, more than half of Americans said they or a family member had been impacted by gun violence such as by seeing a shooting or being threatened, injured, or killed with a gun.

American politicians and regulators have put in place laws and practices that have helped enrich firearm and ammunition manufacturers — which tout $91 billion in economic impact — even as gun violence has terrorized neighborhoods already damaged by white flight, systemic disinvestment, and other forms of racial discrimination.

President Donald Trump championed gun rights on the campaign trail and has received millions from the National Rifle Association, to whose members he promised, “No one will lay a finger on your firearms.” His administration has rolled back efforts under President Joe Biden to address the rise in gun violence.

Emboldened in his second term, Trump is pushing to allow more guns in schools, weaken federal oversight of the gun industry, override state and local gun laws, permit sales without background checks, and cut funding for violence intervention.

Trump ordered the attorney general to review all Biden administration actions that “purport to promote safety but may have impinged on the Second Amendment rights of law-abiding citizens.”

The Biden administration said “a historic spike in homicides” during the pandemic took its greatest toll on racially segregated and high-poverty neighborhoods.

Black youths in four major cities were 100 times as likely as white ones to experience a firearm assault, research showed. Gun suicides reached an all-time high, and for the first time the firearm suicide rate among older Black teens surpassed that of older white teens.

In Bogalusa, the pandemic gun violence spread fear. Among the victims killed were a 15-year-old attending a birthday party and a 24-year-old nationally known musician. Thirteen people were injured at a memorial for a man who himself had been shot. Residents said neighbors stopped sitting in their yards because of stray bullets.

Researchers say communities like Bogalusa endure a collective trauma that shatters their sense of safety. Two years after Forbes’ death, his mother says that when she leaves home her surviving children worry that she, too, might get shot.

Repercussions from the surge will last years, researchers said: Exposure to shootings increases risk for post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, suicide, depression, substance abuse, and poor school performance for survivors and those who live near them.

“We saw gun violence exposure go up for every group of children except white children, in the cities we studied,” Jay said. “Limits on government funding into gun violence research may stop us from ever knowing exactly why.”

Politics of Pain

The year before Forbes died in Bogalusa, Biden signed into law the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, considered the most sweeping firearm legislation in decades.

In a matter of months, Trump has systematically dismantled key provisions.

Efforts to regulate guns have long proven ineffective against the power of political and business interests that fill the streets with weapons. In 2020, the number of guns manufactured annually in the U.S. hit 11.3 million, more than double a decade earlier, according to the federal government. In 2022, the United States had nearly 78,000 licensed gun dealers, more than its combined number of McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and Subway locations, according to Everytown for Gun Safety, an advocacy group.

The Biden administration announced in 2021 it would attempt to reduce gun violence by adopting a “zero tolerance” policy toward firearm dealers who committed violations such as failing to run a required background check or selling to someone prohibited from buying a gun.

The federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF, which licenses gun dealers, has the authority to enforce laws meant to prevent illegal gun sales. In issuing an executive order, the Trump administration declared that, under Biden, the agency targeted “mom-and-pop shop small businesses who made innocent paperwork errors.”

From October 2010 to February 2022, the agency conducted more than 111,000 inspections, recommending revocation of a dealer’s license only 589 times, about 0.5% of cases, an inspector general’s report said. Even when it cited serious violations, the ATF rarely shut dealers down.

ATF leaders told the inspector general’s office that recommendations for license revocations increased after Biden’s zero-tolerance policy was implemented. In April, the Trump administration repealed it.

Surgeon General Vivek Murthy last year declared firearm violence a public health crisis. Within weeks of Trump’s inauguration, his administration removed the advisory. Of the 15 leading U.S. causes of death, firearm injuries received less research funding from the National Institutes of Health for each person who died than all but poisoning and falls, according to an analysis in 2024 by Brady, an anti-gun violence organization. Trump is trying to cut that funding, too.

Trump’s Department of Justice abruptly cut 373 grants in April for projects worth about $820 million, with a large share from gun violence intervention.

“We are going to lose a generation of community violence prevention folks,” said Volkan Topalli, a gun violence researcher at Georgia State University. “People are going to die, I’m sorry to say, but that is the bleak truth of this.”

Asked about its policies, the White House did not address questions about public health considerations around gun violence.

“Illegal violence of any sort is a crime issue, and President Trump has been clear since Day One that he is committed to Making America Safe Again by empowering law enforcement to uphold law and order,” White House spokesperson Kush Desai said.

Trump administration officials “want safer streets and less violence,” Topalli said. “They are hurting their cause.”

Garen Wintemute, an emergency medicine professor who directs the violence prevention program at the University of California-Davis, was among the first in the nation to consider guns and violence as a public health issue. He said race plays a significant role in perceptions about gun violence.

“People look at the demographic risk for firearm homicide and depending on the demographics of the people in the audience, I can see the transformation in their faces,” Wintemute said. “It’s like they’re saying, ‘Not my people, not my problem.’”

Eroding Gun Restrictions

Trump’s incursions against public health efforts to contain gun violence are backed by lobbying power.

Firearm industry advocacy groups made millions of dollars in political donations in recent years, mostly to conservative causes and Republican candidates. That includes $1.4 million to Trump, according to OpenSecrets, which tracks campaign finance data.

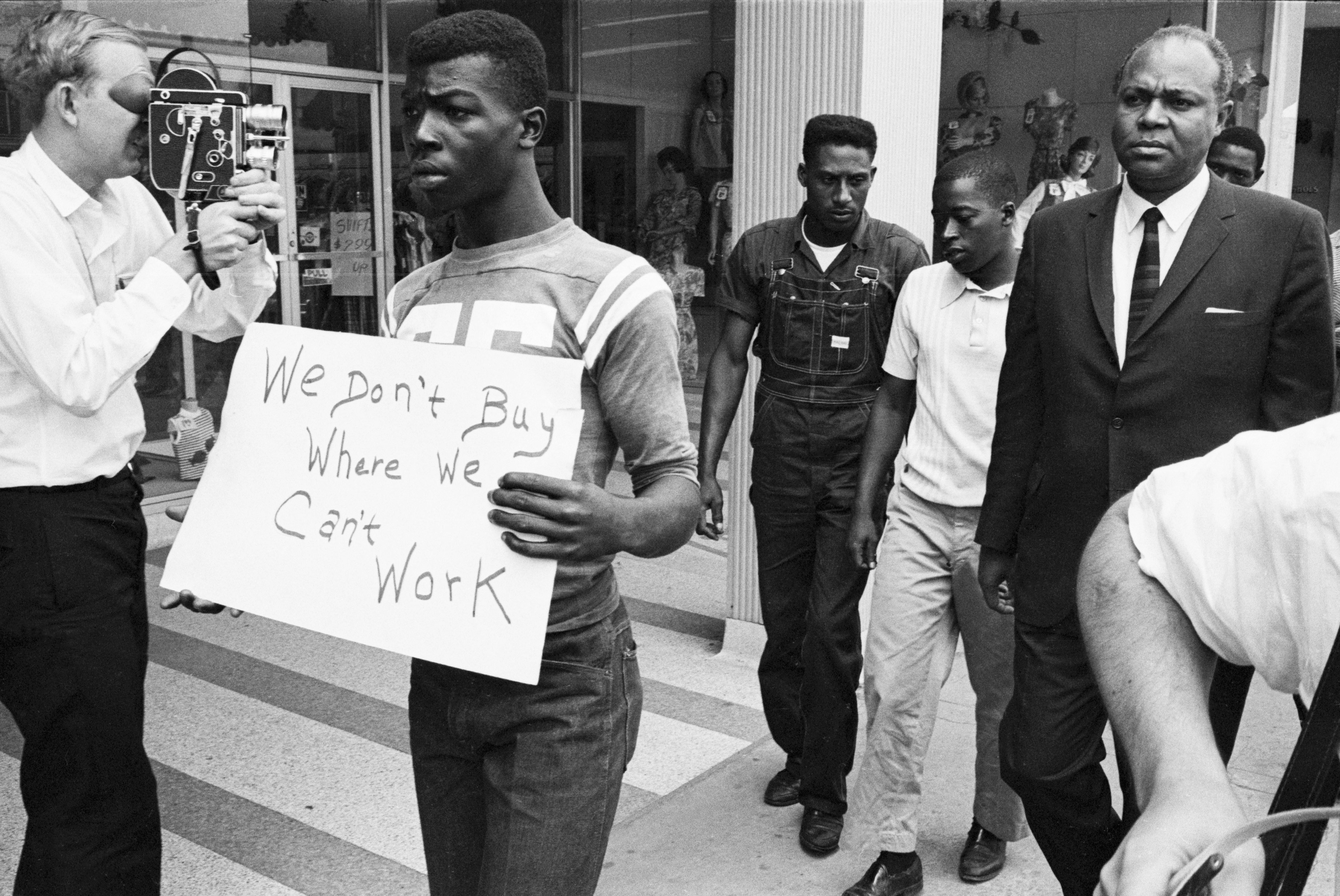

The assassination of civil rights icon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. helped lead to the passage of the federal Gun Control Act of 1968, which imposed stricter licensing rules and outlawed the sale of firearms and ammunition to felons.

While it remains the law of the land, over time, federal and state government actions have significantly weakened its protections.

Most states now allow people to carry concealed weapons without a permit or background check, even though research suggests the practice can increase the risk of firearm homicides.

In Louisiana, Democratic former Gov. John Bel Edwards, in office from 2016 to 2024, vetoed a bill that would have allowed people to carry concealed firearms without a permit.

Elected in 2023, Republican Gov. Jeff Landry signed a law to allow any person over age 18 to conceal-carry without a permit.

The Trump administration has created a task force to implement his executive order to end most gun regulations and which would allow more people with criminal convictions, including for domestic abuse, to own guns.

Figures vary, but some researchers estimate as many as 500 million guns circulate in the U.S. Sales reached record highs during the pandemic and publicly traded firearm and ammunition companies saw profits jump.

Donald Trump Jr. this summer joined the board of GrabAGun, an online gun retailer that went public in July under the stock ticker PEW. In a Securities and Exchange Commission filing, the company, which markets guns to people ages 18 to 44, cited “gun violence prevention and legislative advocacy organizations that oppose sales of firearms and ammunition” as threats to its sales growth.

Dave Workman, a gun rights advocate with the Second Amendment Foundation, said firearms are not to blame for the surge in pandemic shootings.

“Bad guys are going to do what bad guys are going to do regardless of the law,” Workman said. “Taking away gun rights is not going to reduce crime.”

David Yamane, a Wake Forest University sociology professor and national authority on guns, said the U.S. firearm debate is complex and the industry is often “painted with too broad a brush.”

Most guns will never be used to kill anyone, he said. Americans tend to buy more guns during times of unrest, Yamane added: “It’s part of the American tradition. Guns are seen as a legitimate tool for defending yourself.”

‘A Low Level of Hope’

Once called “the Magic City,” Bogalusa has become a grim symbol of deindustrialization.

Bogalusa emerged as Black people formed their own communities in the time of Jim Crow racial segregation at the turn of the 20th century.

Racism concentrated Black people in neighborhoods that became epicenters of poor health, reflected in high rates of cancer, asthma, chronic stress, preterm births, pregnancy-related complications — and, over recent decades, firearm violence.

Thousands flocked to Bogalusa after the Great Southern Lumber Company built one of the world’s biggest sawmills, establishing Bogalusa as a company town. Racial tensions soon followed.

Members of the local Deacons for Defense and Justice gained national attention in the 1960s for protecting civil rights organizers from the Ku Klux Klan, a hate group that burned houses and churches, terrorizing and killing Black people.

As the mill changed hands over the decades, Bogalusa’s fortunes slid. In the mid-20th century, the population surpassed 20,000, but it is now about half that.

International Paper, a Fortune 500 company based in Tennessee, runs the mill as a containerboard factory, employing about 650 people. In 2021, the state announced incentives for the company that included a $500,000 tax break, saying the move would help bring “prosperity.”

Businesses remain boarded up along the main drag. Houses still bear damage from Hurricane Katrina, and many streets are eerily quiet.

Nearly 1 in 3 people in Bogalusa live in poverty — 2½ times the national average.

Bogalusa’s violent gun crime rate reached 646.1 per 100,000 people in 2022, higher than Louisiana’s and 1.7 times the national one, according to the nonprofit Equal Justice USA, citing FBI Uniform Crime Reporting data.

In many rural towns across the South, “there is a level of desperation that is more apparent” than in other parts of the U.S., said Luke Shaefer, a University of Michigan professor of social justice and public policy.

“They don’t have the same infrastructure to have robust social services. People are like, ‘What are my life chances?’” Shaefer said. “People feel like there is nothing that can be done. There is a low level of hope.”

Missed Opportunities

Mayor Truong lamented the violence in Bogalusa after Forbes was killed, writing on Facebook, “When are we as a community going to come together and decide enough is enough?”

The federal government had offered one path forward.

The Biden administration provided billions of dollars to local governments through the American Rescue Plan Act during the pandemic. Biden urged them to deploy money to community violence intervention programs, shown to reduce homicides by as much as 60%.

A handful of cities seized the opportunity, but most did not. Bogalusa has received $4.25 million in ARPA funds since 2021. None appears to have gone toward violence prevention.

The Louisiana legislative auditor, Michael Waguespack, found that Bogalusa used nearly $500,000 for employee bonuses, which his report said may have violated state law. In some cases, the report says, payments were not tied to work performed.

Bogalusa officials did not respond to a public records request from KFF Health News seeking detailed information about its ARPA money.

Former Mayor Wendy O’Quin-Perrette, who served from 2015 through early 2023, told Waguespack in a June 2024 letter that the city used ARPA money to improve streets and pay the bonuses. “We would not have done it without being sure it was allowed,” she said.

O’Quin-Perrette did not respond to requests for comment.

In a 2023 letter to Waguespack, O’Quin-Perrette’s successor, Truong, wrote that Bogalusa officials didn’t know how the federal money was spent. When he took office, Truong alleged, officials discovered “tens of thousands of dollars of checks and cash” stashed “in various drawers and on desks” in city offices.

Truong defended his stewardship of ARPA funds, saying that about $1 million remained when he assumed office but that the money was needed for more urgent sewer infrastructure repairs. “I wish we could have invested more, invested any money in gun violence prevention efforts,” he said.

In an interview, Truong said the city has been “intentional” about bringing down gun violence, including through a summer jobs program. He pointed to statistics that show homicides decreased from nine in 2022 to two in 2024. “If you keep them busy, they won’t have time to do anything else,” he said.

Asked about his January arrest, Truong said he has political enemies.

“I’m the only Democrat in a very red part of the state, and, you know, I’ve made a lot of changes at City Hall, and that ticks people off,” Truong told KFF Health News. He said that he ended long-standing city contracts with local businesspeople. “When you’re shaking up power structures, you become a target.”

Josie Alexander, a Louisiana-based senior strategist for Equal Justice USA, said city officials missed an opportunity when they didn’t use ARPA funds for gun violence prevention. “The sad thing is people here can now see that money was coming in,” she said. “But it just wasn’t used the way it needed to be.”

‘Too Much Trouble Here’

Truong said the city is still reeling from the pandemic spike in violent crime. He said he was at Bogalusa High School’s homecoming football game in 2022 when one teen shot another. Shots rang out, Truong said, and he grabbed his 3-month-old son and “laid in the bleachers.”

“It’s not a foreign topic to hardly anybody in town, whether you’ve heard the gunshots in the distance, whether you have attended a funeral of somebody who passed due to gun violence,” he said. Many still grapple with trauma.

In December 2022, Khlilia Daniels said, she hosted a birthday party for her teenage niece, praying no one would bring a gun.

The hosts checked guests for weapons, she said.

Yet gunfire erupted, Daniels said. Three teens were shot, including 15-year-old Ronié Taylor, who died, according to police.

“When someone you know is killed, you never forget,” said Daniels, 32, who held Taylor until emergency responders arrived.

Tajdryn Forbes was planning his future when he was killed, likely because of a dispute that started on social media over lyrics in a rap song, Guy said.

In a Facebook post in January, Bogalusa police said they had arrested someone in connection with Forbes’ killing. Authorities had previously announced the arrest of a teen in connection with the homicide.

Forbes had been a high school football standout, like his late father, Charles Forbes Jr., who played semipro. When Forbes scored a touchdown, he would look to the sky to honor his dad.

The school praised Forbes for his senior baseball season in a social media post: “This young man makes a difference on our campus and on the field with his strong character.”

When hopes for a college football scholarship did not pan out, Forbes worked as a deckhand for a marine transportation company. He saved money, looking forward to moving to Slidell, a suburb of New Orleans.

“He would always say, ‘There’s too much trouble here’” in Bogalusa, Guy recalled.

kffhealthnews