Alien Constellations: An Atlas Collects the Celestial Worldview of 17 Cultures

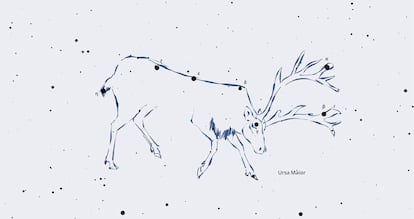

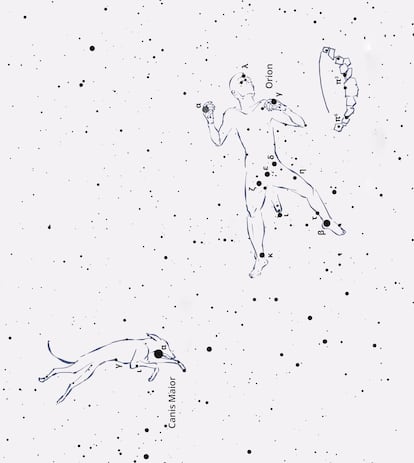

The stars dot the firmament in a chaotic fashion, and since time immemorial, humanity has played with drawing different figures on them. Where the Greeks imagined a great bear, the Egyptians guessed a bull. The Tuaregs, a camel. The Navajos depicted the first man, their own Adam, in this corner of the firmament. The Eskimos drew the figure of a reindeer, and the Incas believed they saw in these seven stars the figure of their founder.

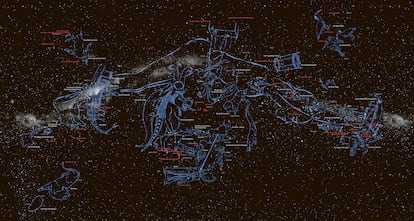

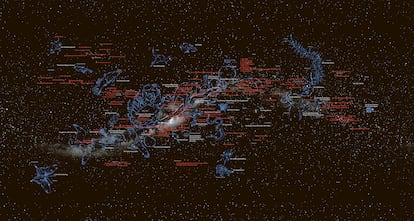

The constellations remain unchanged, but the drawings that dozens of civilizations drew on them, the stories they stored in the sky, were beginning to fade. Austrian philologist, translator, and poet Raoul Schrott spent seven years rescuing them, looking at the sky, but also at the earth, recovering old documents, delving into libraries, and speaking with historians to reconstruct the celestial atlas of 17 cultures. He has compiled them all in a book of more than 1,200 pages entitled Atlas der Sternenhimmel und Schöpfungs mythen der Menschheit (“The Atlas of the Starry Sky and the Creation Myths of Humanity”; no English translation). This is the first time they have been shared.

“Humans only learned to write 15,000 years ago,” Schrott explains over a video call. “The constellations were established long before that, as the first Stone Age hunter-gatherers did.” The writer draws this parallel because he believes that, lacking letters, our ancestors turned to the stars to write humanity's first stories. “It was a way of passing on knowledge to the next generations,” he explains.

The stars also hold lessons, often of a sexual or moral nature. The Big Dipper was a nymph, Callisto, transformed into an animal for having a relationship with the god Zeus while he was married. This handful of stars has served for millennia to subtly remind women that sex is best within marriage. There are other similar stories. Incest, infidelity, love affairs...

It's curious that when faced with something as grand and transcendent as the firmament, many people see it as a place to reflect their instincts and passions. "The constellations are part of a universe that is too vast, too cold, distant, and incomprehensible for the human mind," Schrott reflects. "But on the other hand, we have drawn our own little human stories within them; we have preserved myths and tales." It is this double face that caught his attention and led him to begin his project.

Not all stars represent spicy or romantic stories. Death and eternal life are recurring themes in all cultures. These are naturally combined with more earthly matters, such as practical information about their animals, plants, or the ideal time to hunt. “The celestial vault functions like a natural Sistine Chapel,” Schrott summarizes. “Ancient civilizations deposited all the aspects that were central to their culture up there. So, if you want to know how Babylonian, Boro Boro, or Maori society worked, you just have to look at the sky, because it functioned for them like a schoolbook.”

The truth is, it would be better to do so with Schrott's book in hand. His work isn't unique; there are notable precedents. Specific initiatives like the Australian Aboriginal Astronomy Project , which brings together academics, educators, and elders from Indigenous Australian communities to research and document traditional astronomical knowledge from the area. In Peru and Bolivia, there are dozens of organizations dedicated to recovering the astronomical legacy of the Incas . And they take people to planetariums or on tours to show them the constellations. "The problem is they don't have the drawings to do it," Schrott laments. Or rather, they didn't, since now they can use the ones in his book, which he has donated to these kinds of initiatives.

There were also treatises prior to Schrott's, such as Anthony Aveni's Stairways to the Stars (1997, not translated into Spanish), which reviewed the skies of three great cultures of the past. But few have had such detailed illustrations, and none have documented so many worldviews; no one had ever shared them until now.

The Tuaregs of the Sahara, the Australian Aborigines, or the Filipinos of Palpaba Island. The Pora of Bora Bora, the Maori of New Zealand, the Eskimos, the Bushmen, the Inuit, the Navajos, the Apaches, the Mayans. The Andean tribes and the Boro Boro of Brazil. All of them appear in Schrott's atlas, which doesn't talk so much about the stars as about the people who gaze at them. The humanist documented up to 17 skies around the globe. "It's the minimum number to give a view from the entire world," he explains. From different latitudes, sensibilities, and historical moments. These were also the only celestial worldviews he was able to fully document, as many have been lost forever.

“The most beautiful thing was realizing that each culture saw completely different things in the same sky,” the author comments. Explaining the differences is easy: first, depending on our position on Earth, we see different portions of the sky. There are constellations exclusive to the northern hemisphere, such as Ursa Major, Cassiopeia, or Cepheus. Others are only visible in the south, such as the Southern Cross or Centaurus. And there is a third group of constellations close to the equator, such as Orion or Sagittarius, which are shared by both hemispheres, but are seen in a different direction, almost upside down, depending on where you look at them.

Finally, paraeidolia comes into play , the human tendency to find familiar shapes in random images, such as when clouds look like sheep or you think you can see Jesus Christ or Elvis on a piece of toast. Something similar happens when looking at the stars: people see shapes that look familiar. Since wildlife varies across the globe, night-sky observers would connect the stars by drawing pictures of camels, reindeer, sharks, or turtles, depending on which animal they were most familiar with.

Schrott is pleased with his endeavor; one can sense a certain pride in him as he takes his enormous book to show it on camera. But he regrets that it wasn't someone else, centuries ago, who decided to write it down. "Many of the stories that were in heaven have already been lost," he explains. "This should have been done at least 100 years ago, when oral tradition kept them alive."

His job was to draw on those who had begun to do so, combing through old books and documents to uncover any information. In this regard, the author highlights the work of some Spanish missionaries. “Amidst all the horror of colonialism, we found this small positive, a couple of people who did something important to preserve the culture of those lands, instead of imposing their own. They wrote celestial myths of the Mayans and Incas, information that would have been lost without them,” he explains.

This is not the only episode that stands out about Spain. The author recounts how the pioneering scientific cooperation between Muslims, Jews, and Christians that took place in the country at the end of the Middle Ages was key to the formation of modern constellations.

However, Schrott's atlas distances itself from the Eurocentric perspective, and only briefly mentions the current official constellations, which are already abundantly documented. "Our sky is an atypical sky, because it's a cultural appropriation," the expert notes. "Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs... In the European sky, you can see traces of all the great civilizations that have passed through here," he summarizes.

In the end, it was this hybrid sky, made from the scraps of other cultures, that ultimately prevailed. Schrott's atlas reflects the stories of tribes long extinct, or diluted by a terrestrial globalization that has spread to our heavens.

In 1919, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the world's only recognized authority for naming stars, constellations, moons, and planets, was founded. Three years later, it officially defined the 88 constellations that cover the entire sky visible from any point on Earth. In 1930, the IAU established the official boundaries of each constellation and drew the borders of the celestial map. The sky is divided into these 88 defined zones; there is no room for new discoveries visible from Earth, nor for the creation of new stories and myths. With powerful telescopes, new stars, galaxies, and clusters are gradually being discovered. The IAU catalogs them with technical names like VVVX 03 or DELVE 6. No one makes up stories about them, because they cannot be seen with the naked eye.

The sky may be a less evocative place today. All the constellations may have been seen, claimed, and named centuries ago. But there are many stories to be discovered within them. The stars are the same, but the myths that each civilization preserved within them are completely different. No one looks at the sky and composes constellations anymore, which is normal, Schrott acknowledges. But they also don't appreciate those of their ancestors; few people even know how to differentiate between those of their own culture. "From the city, you can barely see them," he says. "And I think this is dangerous because the stars have a powerful psychological effect. When people look at the sky, they realize how small and insignificant they are. If we stop looking at it, we will not only forget the stories of our ancestors. We may also forget our place in the universe."

EL PAÍS