The scientist who knows how to kill a person, but wants to remove only part of their cells

Chemical engineer Jesús Santamaría believes that scientists are better at murdering. “They're used to observing, to drawing conclusions. They can understand the deductive process of a detective, so the crimes they commit are more interesting and harder to detect,” he maintains.

"Do you think you would know how to kill better than someone else?"

―Sure. Absolutely, absolutely.

Santamaría, born in Burgos 66 years ago, has a unique profile. He is writing his third crime novel, about a serial killer scientist, and has received more than five million euros from the European Research Council to try to cure cancer. Killing a person is simple on paper, but killing only a portion of their cells, the cancerous ones, is the great challenge in medicine. Santamaría emphasizes that he was born in 1959, the same year that the famous American physicist Richard Feynman gave a lecture considered the founding milestone of nanotechnology, the manipulation of matter at the scale of millionths of a millimeter. Feynman, one of the fathers of the atomic bomb, mentioned “a very crazy idea” from a friend of his. “In a surgical operation, it would be very useful if you could swallow the surgeon . You place the doctor inside a blood vessel, he goes to the heart and observes the surroundings. […] He identifies which valve is defective and operates on it with a small scalpel,” the physicist proclaimed.

The idea stopped being crazy a long time ago, explains Santamaría in his office at the Institute of Nanoscience and Materials of Aragon, in Zaragoza. The first nanomedicine, called Doxil , has been used since 1995 to treat various types of cancer. It's simply a chemotherapy compound—doxorubicin, obtained from bacteria—encapsulated in fatty spheres. The resulting molecules are sized to circulate through the bloodstream until they encounter the characteristic pores of a tumor's blood vessels, deformed by the rapid growth of the cancer. With a simple nanotechnology trick, the medicine reaches the diseased areas more specifically.

“It's been exactly 30 years since the first nanomedicine. People then thought, 'This is great. We've finally eradicated cancer! If we can achieve this with a silly passive system, what can't we achieve by attaching the medicine to monoclonal antibodies [proteins created in the laboratory to directly target cancer cells]!' And what has happened since then? The drug doesn't reach the cells,” Santamaría laments.

German chemist Stefan Wilhelm measured the magnitude of the failure in 2016. After reviewing all the experiments published over a decade, he observed that barely 0.7% of the nanoparticle dose injected into a patient actually reached the tumor. Apparently excellent nanodrugs for killing cancer cells already exist, but they don't reach their destination. "That's the Gordian knot. If we solve it, we've got it," proclaims Santamaría. The European Research Council has just awarded him one of its prestigious Advanced Grants, a budget of €3.1 million to try to find a solution to the problem. This is his third European grant of this type, a milestone achieved by only five other scientists in Spain.

The researcher presented his first crime novel, Akademeia (The Books of the Black Cat), in 2018. In it, a young Spanish scientist emigrates to the United States to work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and encounters a ruthless ego struggle and a corpse. “Scientists are often considered benevolent beings, dedicated to their exotic research, removed from worldly passions. But researchers are human beings, subject to the same passions as everyone else and capable of the same misdeeds,” the author warns on the back cover.

Locked down by the COVID pandemic, he wrote his second crime novel: Inmortal (Los libros del gato negro), in which, once again, the protagonist is a Spanish researcher at MIT who confronts a messianic scientist who has founded a new religion and seeks immortality. “These are pure crime novels. No one should expect dead bodies on the first page. When I kill someone, you already understand the killer perfectly and you almost agree that I should kill them,” the author says, laughing.

It's no coincidence that the crime scene is MIT, one of the world's temples of science. Santamaría entered politics in Aragon in 2003, as Director General of Research in the regional government of Marcelino Iglesias (PSOE). In 2007, after his resignation, he went to spend a sabbatical year at MIT under the direction of Robert Langer , the guru of intelligent drug delivery and one of the world's greatest drug inventors. In 2010, Langer founded Moderna with other colleagues, which would end up producing one of the first effective vaccines against COVID-19, saving millions of lives .

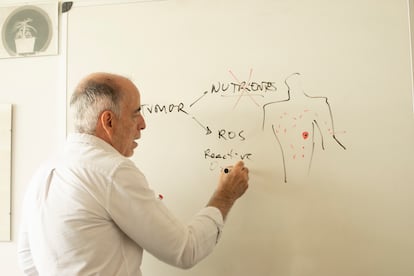

With its first European grant, €1.85 million in 2011, Santamaría's team developed catalysts for the hydrocarbon industry. With its second grant, almost €2.5 million in 2017, it produced other catalysts that, when activated, generate toxic substances in cancer cells, destroying them from within : by starving them of their food—"They're real glucose junkies"—by nullifying their essential antioxidant molecules or by supplying them with inactivated drugs that reactivate at will. Santamaría affirms that the results in mice are promising, despite the fact that, as the animals are sacrificed after each experiment, up to 98% of the nanoparticles are trapped in the liver, failing to reach the tumor.

With his third grant, worth 3.1 million euros, Santamaría will tackle the Gordian knot: the patient's own immune system. The vast majority of nanoparticles end up captured by the white blood cells present in the liver's blood vessels. His team's first strategy is to design harmless decoys that detain these white blood cells before injecting the curative nanoparticles. Once human defenses have been evaded, they must reach the tumor. "Our next strategy is that of the Trojan horse ," he explains, recalling the legend of the entry into the fortified city thanks to a seemingly harmless wooden horse, but filled with Greek soldiers.

Tumor cells communicate through extracellular vesicles, a few millionths of a millimeter in size. The ultimate goal of Santamaría and his colleagues would be to take a sample of a patient's cancer, grow the tumor cells in the laboratory, harvest the vesicles, load them with curative nanoparticles, and reinject them into the patient after administering the decoy particles. "We want to test the concept in a mouse with its complete immune system. If it works, and instead of 1% of the nanoparticles reaching the tumor, 50% will reach it, shouts of joy will be heard all the way from Madrid. If we succeed, we will look for a pharmaceutical company willing to participate in human clinical trials," explains Santamaría, also a professor at the University of Zaragoza.

Santamaría is finishing his third crime novel, again set at MIT. This time, a researcher unjustly expelled from the institution decides to take revenge and becomes a serial killer of scientific journal editors . The Burgos-born nanotechnologist imagines innovative ways to kill in his spare time, but dedicates his workday to finding the key to exterminating only the unwanted cells of a person, saving their life. "It would be realizing Feynman's 1959 vision: reducing the size of the doctor so he can enter our bodies, wander around looking for things to fix, and then fix them," he concludes.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F833%2F2a0%2F1c9%2F8332a01c9c58d9c0f0f0876c363f181b.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fc7c%2F4f8%2Ffd0%2Fc7c4f8fd05e6d44f7bf2c52eb7e4bb7b.jpg&w=1280&q=100)