Feeling mentally exhausted? Brain areas that control whether people give up or persevere have been identified.

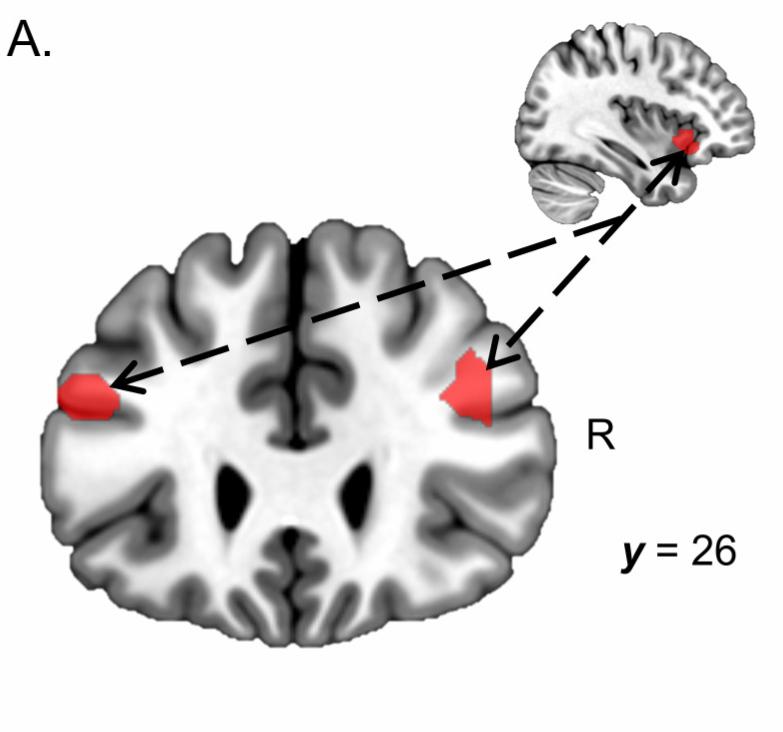

In experiments with healthy volunteers undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging, scientists have discovered increased activity in two areas of the brain that work together to react to, and possibly regulate, the brain when it 'feels' tired and abandons or continues a mental effort.

The experiments, designed to help detect various aspects of brain fatigue , could help doctors better assess and treat people experiencing overwhelming mental exhaustion, including those with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) , the scientists say.

A report on the study, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), was published online in the Journal of Neuroscience . It details the results of 18 healthy adult female and 10 male volunteers who were assigned memory-training tasks.

"Our lab focuses on how [our minds] generate value for effort," says Vikram Chib, Ph.D., associate professor of biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and a research scientist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute. "We understand less about the biology of cognitive tasks, including memory and recall, than we do about physical tasks, even though both are effortful." Anecdotally, Chib says, scientists know that cognitive tasks are tiring, and relatively less about why and how that fatigue develops and plays out in the brain.

The 28 study participants, aged between 21 and 29, were paid $50 to participate in the study and were told they could receive additional payments based on their performance and choices. All participants underwent a baseline MRI before beginning the experiments.

Two areas of the brain may work together to indicate when you're feeling tired. Photo: iStock

Their working memory tests, which were conducted while they underwent MRI scans of their brains, involved looking at a series of letters, in sequence, on a screen and recalling the position of certain letters. The further back a letter was in the series, the more difficult it was to recall its position, which increased cognitive effort. Participants received feedback on their performance after each trial and had the opportunity to receive increasing payments (from $1 to $8) with more difficult recall exercises. Before and after each trial, participants were required to self-report their level of cognitive fatigue.

"Our study was designed to induce cognitive fatigue and see how people's decisions to exert effort change when they experience fatigue, as well as to identify the locations in the brain where these decisions are made ," says Chib.

In particular, Chib and his research team members Grace Steward and Vivian Looi found that financial incentives had to be high for participants to exert greater cognitive effort , suggesting that external incentives drove such effort.

"This result didn't entirely surprise us, as we had observed the same need for incentives to stimulate physical effort in previous work," Chib says.

"The two brain areas may be working together to decide to avoid further cognitive effort unless more incentives are offered. However, there may be a discrepancy between perceptions of cognitive fatigue and what the human brain is actually capable of," Chib says.

According to Chib, fatigue is linked to many neurological conditions, such as PTSD and depression. "Now that we've likely identified some of the neural circuits of cognitive effort in healthy people, we need to look at how fatigue manifests in the brains of people with these conditions," he adds.

Chib says it might be possible to use medication or cognitive behavioral therapy to combat cognitive fatigue , and that the current study, which uses decision tasks and functional magnetic resonance imaging, could serve as a framework for objectively classifying cognitive fatigue.

Connection between the insula and the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex resulting from cognitive fatigue. Photo: Vikram Chib, Johns Hopkins Medicine and KKI

Functional MRI uses blood flow to measure broad areas of activity in the brain; however, it does not directly measure neuronal activation or more subtle nuances of brain activity.

"This study was conducted in an MRI scanner and with very specific cognitive tasks. It will be important to see how these results generalize to other cognitive efforts and real-world tasks," Chib says.

See also

Protecting the Brain from Alzheimer's | El Tiempo Photo:

eltiempo