A seismometer in every pocket: five million mobile phones received an alert seconds after the Almería earthquake.

For the first time, an earthquake warning reached the Spanish population before the actual shaking. Millions of people received it on their Android phones at dawn last Monday , causing shock that spread across social media. The shock was even greater when it was revealed that it was their smartphones themselves that had detected the earthquake and issued the alert, rather than a sophisticated network of seismometers.

With minor material damage and no casualties, the main cause of the earthquake off the coast of Almería— magnitude 5.3 according to the National Geographic Institute (IGN) —was the early warning sent by Google without official data or waiting for approval from the authorities. But it wasn't a stealth test or a pilot project. This Thursday, coincidentally, the system used since 2021 by the American technology giant around the world received significant support from the scientific community: the journal Science , a showcase for the world's best science, has just published research demonstrating its effectiveness in anticipating destructive earthquake waves and, thus, helping to mitigate their damage among the population.

“Earthquake nearby. Prepare for light tremors.” It was 7:13:39 last Monday when a multitude of Android phones in southeastern Spain began receiving this unprecedented alert, which estimated—with relative accuracy—the magnitude of the earthquake at 5.1. According to data provided by Google to EL PAÍS, when the first warning was issued, just 12.5 seconds had passed since the earthquake began, near the coast of Almería and 3 kilometers beneath the Mediterranean Sea. In total, five million phones ended up receiving an alert in the following moments, the technology company claims.

How was this possible? Richard Allen, the father of the innovative seismic alert system that uses smartphones ' own sensors to anticipate tremors and jolts, explains to this newspaper: "About 5.5 seconds after the estimated origin of the earthquake [which the IGN places at 7:13:27, local time], the first waves reached the phones in the nearest city," reveals this seismologist, who is also the lead author of the study published in the journal Science . In that article, he details that the seismic early warning system takes advantage of the fact that these first disturbances, the P waves, travel much faster through the subsoil than S waves, which are responsible for the strongest jolts and have a greater destructive capacity.

There's a margin, but it's narrow. Every second counts. "Approximately 10 seconds after the earthquake began, the S-waves reached the nearest town. So the first alert was delivered a couple of seconds later, but it was before the S-waves reached more distant locations," Allen explains. All smartphones are potential earthquake detectors, because they have location, tilt, and acceleration sensors that sense seismic disturbances and can communicate them instantly using their data connection. A decade ago, Allen and his team at the University of California, Berkeley's Seismological Laboratory (USA) thought about taking advantage of this innate capacity of mobile phones. Today, all new phones running Android—the mobile operating system developed by Google—have the seismic alert function activated by default. And Google's servers are constantly listening: when they begin to receive signals of possible seismic disturbances, their algorithms process them until they accumulate enough evidence to trigger an alert.

Marc Stogaitis, Android's lead software engineer and co-author of the study, explains that waiting for more mobile phone sensors to detect the earthquake may make the magnitude estimate more accurate, but it also reduces the timeframe for issuing the warning. "You have to find the right balance between accuracy and time—that's the challenge for any earthquake early warning system. And on top of that, our system has to handle signals from many different phone models, with varying sensor qualities."

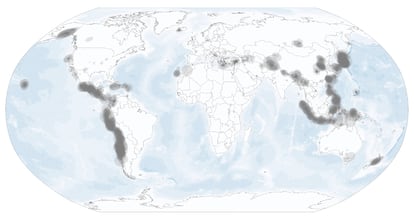

Warn before destructive wavesThe Android earthquake alert system began rolling out in the first countries—Greece and New Zealand—in April 2021 and then expanded to a total of 98 countries. Now, Allen and Stogaitis have published a scientific review of the first three years of operation. By March 2024, Google sent alerts for a total of 1,279 suspected earthquakes—those detected with a magnitude greater than 4.5—and the analysis shows how the accuracy of the estimated magnitude has been improving since the initial tests. Thus, mobile earthquake detection has managed to match, and even slightly improve, the margin of error of the national early warning systems of the US and Japan, which do use the extensive public seismometer networks in those countries. In addition, the researchers evaluated the usefulness of the alerts by conducting satisfaction surveys with the people who received them. Of the more than one and a half million respondents, 36% said they received the alert before the earthquakes hit, 28% during the earthquake, and 23% after.

Google's algorithm for sensing the arrival of earthquakes isn't infallible: it has sent three false alerts, which researchers say were due to two storms and the mass sending of a notification that vibrated many phones at the same time. The study of these events led them to refine the system to prevent such an event from triggering an alert again. As a success story, Allen and Stogaitis present a severe earthquake—magnitude 6.7—that occurred south of the Philippines on November 17, 2023. "Nearly 2.5 million people received an alert. Of these, more than 100,000 received a warning to take protective measures, which in most cases arrived a few seconds before the S waves and the peak of maximum intensity shaking," the researchers state in their scientific article. These high-level protection alerts are more than just notifications—like the ones last Monday in Almería—they bypass the phone's silent or do not disturb settings, fill the entire screen, and emit a distinctive, loud sound.

Unlike the success of the Philippines, the devastating double earthquake in Turkey and Syria on February 6, 2023, exposed one of the Achilles' heels of this system, which greatly underestimated the magnitude of the earthquakes. "It's a physical problem that any early warning system suffers from in the face of a very intense earthquake, even those based on high-precision seismometers," explains seismologist Juan Vicente Cantavella, who did not participate in the study and is the director of the National Seismic Network at the IGN in Spain. This expert assesses the results of the Android seismic warning system as a very positive advance "despite this and other limitations that the researchers point out in their article." Smartphones cannot detect earthquakes that occur in the middle of the ocean, as the low sensitivity of their sensors limits their range to a distance of between 100 and 200 kilometers from the coast. The system developed by Berkeley and implemented by Google is also ineffective in sparsely populated areas, where there are not enough mobile phones for accurate detection.

Towards a public alert systemCantavella is concerned that these innovative seismic alerts are being sent by a private company: "Whose responsibility is it if these alerts give false alarms or if they don't reach certain users?" Elisa Buforn, a recently retired professor of seismology at the Complutense University of Madrid, is one of those Android users who didn't receive the alert last Monday, even though she was "in an area where other people did." Despite this, Buforn praises the work of Allen, Stogaitis, and their teams and considers it good news that they have managed to demonstrate that " smartphones can help with early earthquake warnings."

At Google, Marc Stogaitis claims that his system is "a complementary tool to the existing infrastructure; it is not intended to replace official seismic detection or warning systems." He only proposes it as an alternative for countries with fewer resources, which lack national seismic networks. Spain does have one, recalls Cantavella, who is responsible for it, and states that the implementation of a public earthquake early warning system is being studied. "The priority would be to focus on alerting about earthquakes occurring in the same area of the Atlantic where the great earthquake that devastated Lisbon in 1755 originated." There, sooner or later, another major earthquake is sure to occur.

Buforn agrees with this priority and recalls that her laboratory has developed " two different seismic early warning systems —for now, only intended for scientific use—and has demonstrated their viability in anticipating tremors generated in that area south of the Peninsula," from Cape St. Vincent to both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar. This veteran seismologist, who has dedicated a good part of her career to studying and promoting seismic early warnings, celebrates that Google's initiative can "serve to make people aware of the existence of these systems that can mitigate the effects of some earthquakes. Really, for us to have these official alerts in Spain, all we need is for society to demand it. We have the means." However, despite her optimism about this recent technology—for now, implemented mainly in wealthy countries with a high seismic risk—she recalls its limitations: " In the face of an earthquake like the one in Lorca in 2011, so shallow and located right beneath the city, no warning system would have been of any use."

EL PAÍS